1. Lunar and solar zodiacs

2. Sidereal and tropical zodiacs

3. Saptarishis and nakshatras

4. Calibrating the calendar

5. Kali-yuga and Magha

6. Indian antiquity

Just as the sun, as viewed from earth, passes through the 12 constellations of the solar zodiac in the course of a year, so the moon passes through different star groups or asterisms – also known as lunar mansions – as it orbits the earth. The moon takes about 27.32 days to return to the same point in its orbit as viewed against the background of stars; this is known as the sidereal lunar month. Hindu astronomers, like other ancient stargazers, divided the path of the moon’s orbit into 27 (or sometimes 28) lunar mansions, which they called nakshatras. Like the constellations of the solar zodiac, the mansions of the Hindu lunar zodiac are centred on the ecliptic (the plane of the earth’s orbit around the sun), since the moon’s orbit is tilted at only about 5° to the ecliptic.

There are several versions of the Hindu lunar zodiac. If the ecliptic is divided into 27 nakshatras, each spanning 13°20', the moon stays a little over a day in each one. Sometimes a smaller interval is assigned to a 28th nakshatra (Abhijit), so that the moon stays one day in each of 27 nakshatras and about 0.3 days in the 28th. In other systems, the 27 nakshatras are assigned unequal widths. The Surya Siddhanta refers to 27 nakshatras of equal width (ch. 2, v. 64), but it also provides details of 28 nakshatras, distributed very unevenly along the ecliptic (ch. 8).1

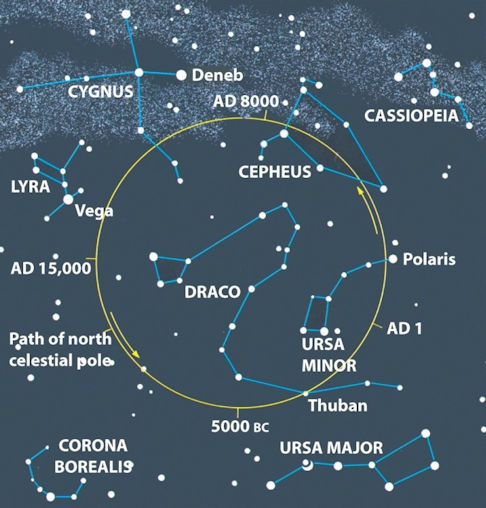

Solar and lunar zodiacs. (tamilandvedas.com)

In modern times, Ashvini (represented by a horse’s head) is considered the first nakshatra, but there are Hindu texts indicating that Rohini, Krittika and other nakshatras were once the first.2 This is related to the precession of the equinoxes (Poleshifts, 1:3): the position of the sun at the time of the equinoxes and solstices shifts slowly westward through the ecliptic constellations, taking 25,920 years to complete a full circuit of the zodiac.

References

There is an important distinction between the sidereal (fixed) and tropical (moveable) lunar or solar zodiacs. The distinction is the result of precession.

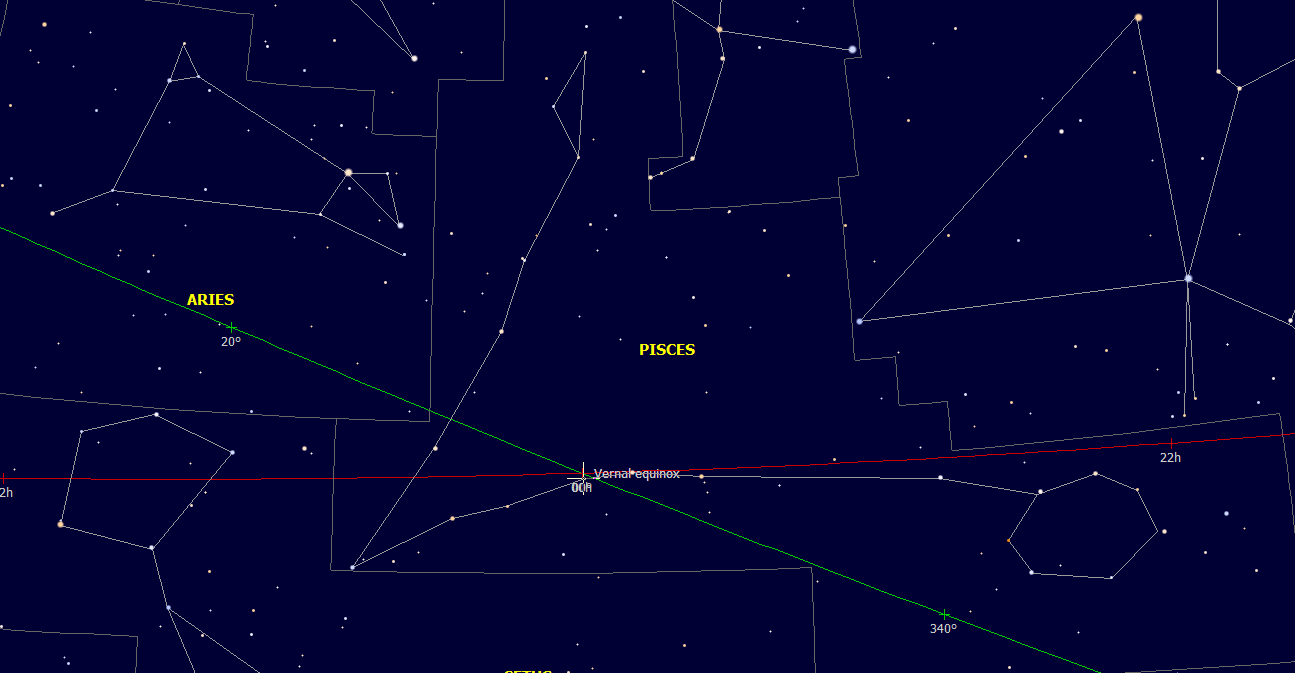

The sidereal solar zodiac comprises the actual star constellations in space (Aries, Pisces, Aquarius, etc.). The 12 constellations are also called the houses or mansions of the zodiac. The tropical solar zodiac, on the other hand, comprises the astrological signs of the zodiac; these have the same names as the constellations but are regions around the earth, with the spring (or vernal) equinox always marking the start of the sign Aries.1 In other words, the spring equinox always marks 0° of the sign Aries, regardless of which zodiacal constellation the sun is actually in at that moment. Nowadays, the sun is located in the constellation Pisces, approaching the boundary with Aquarius, at the spring equinox.

Position of the sun at the vernal equinox in 2022, showing the celestial equator (red) and the ecliptic coordinate grid (green). (CyberSky 5.2)

Just as the spring equinox always marks 0° Aries in the tropical solar zodiac, so it always marks 0° Ashvini in the modern version of the Indian tropical lunar zodiac, whatever the actual lunar mansion that the sun is then in. The tropical lunar mansions can also be called the lunar signs.

References

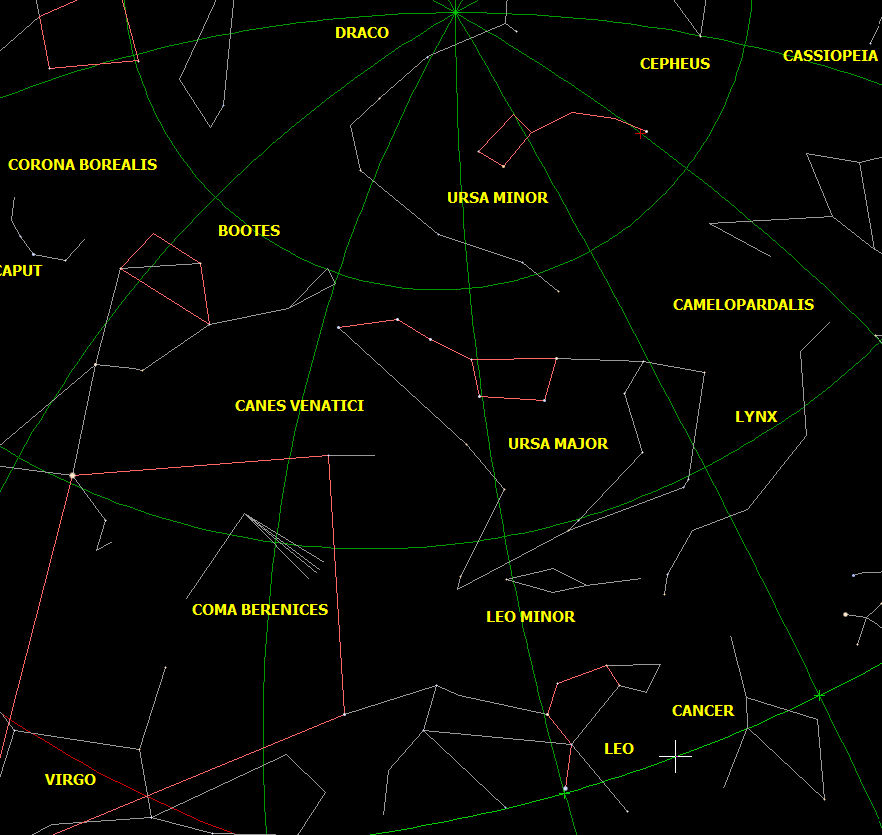

In Hindu astronomy, the saptarishis (seven sages) are the seven brightest stars of Ursa Major (the Great Bear), which form the asterism known as the Big Dipper or the Plough.

Ursa Major. Mizar and Alcor are double stars. (Stellarium)

Several ancient Indian texts state that the saptarishis move through the nakshatras at the rate of one lunar mansion in 100 years. Taken literally, this is nonsense: there is no significant change in the angular distance between the saptarishi stars and the stars around the ecliptic from year to year. Although every star undergoes its own proper motion, all the stars outside our solar system are at such immense distances that their position in relation to one another barely changes even over the course of many millennia.

According to the Vishnu Purana: ‘When the two first stars of the seven Rishis (the Great Bear) rise in the heavens, and some lunar asterism is seen at night at an equal distance between them, then the seven Rishis continue stationary, in that conjunction, for a hundred years of men.’1 This is the Wilson translation. The Dutt translation omits the words ‘between them’, making the sentence more ambiguous.2 The first two stars in Ursa Major that rise are Dubhe (Alpha Ursae Majoris) and Merak (Beta Ursae Majoris).

As explained below, there are three different ways of interpreting the above quotation.

References

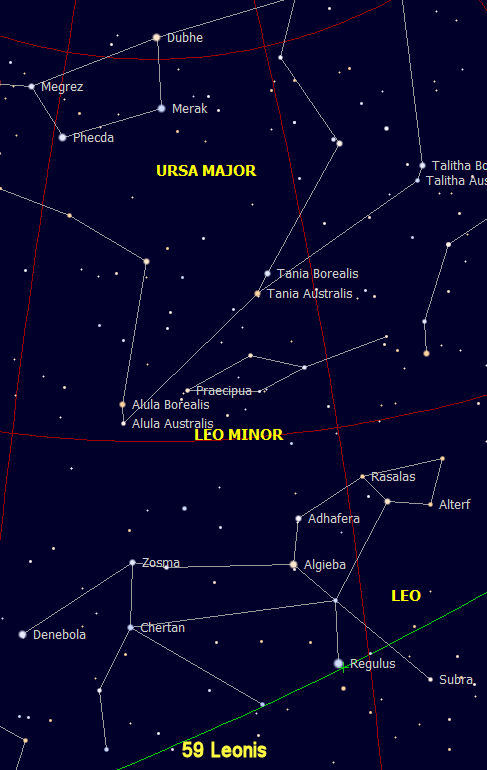

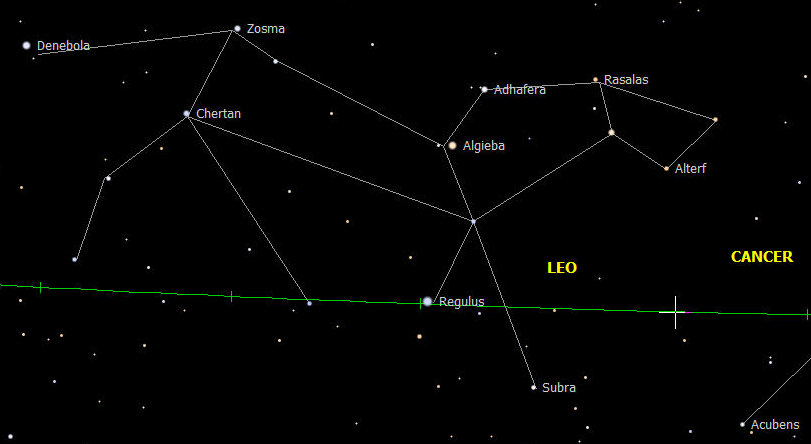

The first interpretation, put forward by Indrasena,1 for example, is that a line is drawn from Dubhe to Merak and acts as a pointer. When extended southwards, it intersects the ecliptic in the constellation Leo, very near the star 59 Leonis. This point lies in the nakshatra Purva Phalguni, whose principal star is Chertan (Delta Leonis).

59 Leonis is located just below the ecliptic (green line), to the

left of the label. The celestial coordinate grid is shown in red.

Because the stars are relatively stationary, the point where the Dubhe-Merak line intersects the ecliptic changes by no more than a degree or two, even over the course of thousands of years. What does, however, change significantly is the angular distance between the intersection point on the ecliptic and the vernal equinoctial point, which is constantly shifting due to precession. So while the pointer always remains in Purva Phalguni in the sidereal lunar zodiac, it moves through the tropical lunar zodiac at an average rate of 50 arcseconds per year – equivalent to 1° in 72 years, 960 years per lunar mansion, and 25,920 years for a complete precessional cycle.

Ursa Minor, Ursa Major, and the north celestial and ecliptic poles.

At present, if the Dubhe-Merak pointer is extended northwards, it passes very close to the current north celestial pole, which is about 0.6° from the current polestar (Polaris/Alpha Ursae Minoris). Merak and Dubhe are in fact commonly called the ‘pointer stars’ precisely because they point towards Polaris. This situation is not permanent, because the north celestial pole moves entirely around the north ecliptic pole (located in Draco) in the course of a precessional cycle. Polaris moved to within 5° of the north celestial pole around 1200 CE. Before that, the last star to be located near the north celestial pole was Thuban (Alpha Draconis), in the third millennium BCE.

The changing polestar. According to theosophy, the earth’s axis does not trace a circle around the

ecliptic pole but a spiral, due to the gradual change in the inclination of the earth’s axis (Poleshifts, 1:4).

In defending his interpretation of the Dubhe-Merak saptarishi pointer, Indrasena argues that ‘at an equal distance’ (Dutt translation of the above quotation from the Vishnu Purana) means that the saptarishi pointer lies roughly halfway between the north celestial pole and the ecliptic. Dubhe and Merak are always about 50° from the ecliptic but are currently only about 30° from the north celestial pole. In 2150 BCE, when Thuban was the polestar, their angular distance from the pole was around 20°, and given that the celestial pole moves entirely around the ecliptic pole in the course of a precessional cycle, the distance can increase to about 65°.

Indrasena also suggests that the reference in the Vishnu Purana to the rishis continuing in the same ‘conjunction’ for 100 years does not mean that they take this period to pass through an entire lunar mansion, but to move one degree along the ecliptic. This would put the rate of precession at 1° per century – the same rate as was estimated by Hipparchus2 (2nd century BCE) and adopted by Ptolemy (2nd century CE). Some writers believe that the later Hindus took this value from Ptolemy, but ancient Hindu astronomers undoubtedly made their own observations (the correct value is 1.39° per century).

Since there are 27 or 28 lunar mansions, the saptarishi cycle lasts 2700 or 2800 years. 2700 years can be transformed into 27,000 years, since adding or removing zeros is common in numerological computations. Since we’re dealing with lunar mansions, this can be read as 27,000 lunar years, which equals 354/365 x 27,000 = 26,186 solar years. If taken as the length of the precessional cycle, this corresponds to a rate of precession of 49.49 arcseconds/year, while the value in 2000 was 50.288"/year. Over time, the rate of precession oscillates around the canonical figure of 50"/year. At present, the rate of precession is increasing, and it would have been 49.49"/year around 1500 BCE.

Notes

Sule et al. argue that the saptarishi pointer always starts from the north celestial pole and passes through the midpoint between Dubhe and Merak; at two points on the path of the celestial pole around the ecliptic pole this line will also pass exactly through Dubhe and Merak.1 This would mean that the saptarishi pointer, or ‘line of the rishis’, is a line of celestial longitude (or ‘right ascension’), equal to the average right ascension of the two stars in question.

The use of the midpoint between Dubhe and Merak in this interpretation is in agreement with the words ‘at an equal distance between them’ in the Wilson translation of the above quotation from the Vishnu Purana. Wilson also quotes the following explanation by Sridhara Swami, a commentator on the Bhagavata Purana:

The two stars (Pulaha [Merak] and Kratu [Dubhe]) must rise or be visible before the rest; and whichever asterism is in a line south from the middle of those stars is that with which the seven stars are united; and so they continue for one hundred years.2

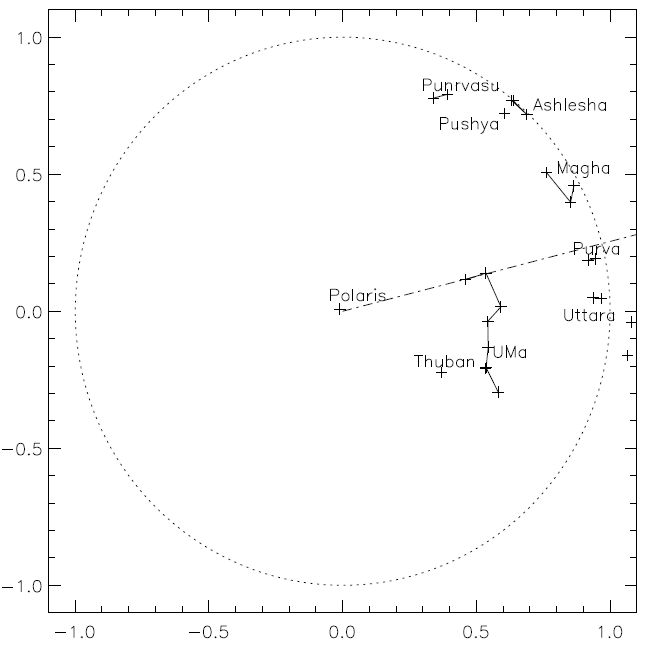

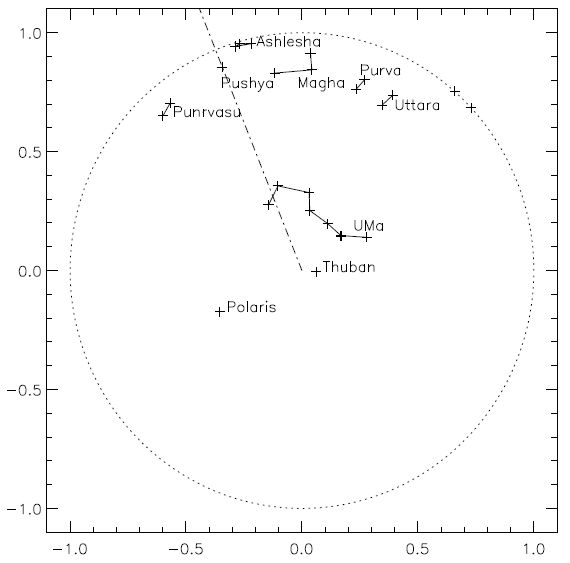

The figures below show the position of Sule et al.’s saptarishi pointer in 2000 CE, and also in 2150 BCE, when Thuban was the star nearest the pole.

Position of the pointer in 2000 CE. The celestial pole is at the centre of the figure.

The dotted line represents the celestial equator. The pointer intersects Purva Phalguni.

In 2150 BCE the pointer was in the nakshatra Pushya (in Cancer).

Sule et al.’s approach differs from Indrasena’s in that the saptarishi pointer does indeed move through the sidereal nakshatras due to precession. But it is unsatisfactory because the pointer does not move through all the nakshatras in the course of a precessional cycle, but back and forth through only four or five of them, spanning about 60 degrees (this can be seen by drawing a line from any point on the precessional path of the celestial pole through the midpoint between Dubhe and Merak). Moreover, the pointer can take from a few hundred years to over 1000 years to pass through a nakshatra, depending on how close the celestial pole is to Dubhe/Merak (the closer it is, the less time it takes) and on the exact width of each nakshatra.

References

John Bentley (1825) put forward a third way of understanding the saptarishi pointer, or line of the rishis: it begins at the north ecliptic pole and passes through Merak (Beta Leonis), but not through Dubhe.1 Like Indrasena’s version of the Dubhe-Merak pointer, this line, too, intersects the ecliptic in the constellation Leo, but in the nakshatra Magha rather than Purva Phalguni. Magha (principal star: Regulus) borders Purva Phalguni, and according to the diagram of the lunar zodiac in section 1, it begins at the boundary between Cancer and Leo.

Bentley’s scheme could be modified slightly so that the pointer is the line joining the ecliptic pole and the midpoint between Dubhe and Merak (rather than only Merak), which would be in accordance with the earlier quotation from the Vishnu Purana. In both cases, the line of the rishis is a line of ecliptic longitude, and intersects Magha.

The cross on the ecliptic between ‘Leo’ and ‘Cancer’ shows where a line drawn from the

north ecliptic pole through the midpoint between Dubhe and Merak crosses the ecliptic.

Closeup of Leo.

In contrast to the first two approaches, the midpoint between Dubhe and Merak is almost exactly halfway between the ecliptic pole and the intersection point on the ecliptic, and this situation remains the same for millennia, since the ecliptic pole barely moves and the stars are relatively stationary.

Bentley says that the line of the rishis is ‘invariably fixed to the beginning of the lunar asterism Magha’, in the sense that the point where it intersects the sidereal nakshatra Magha does not move significantly for thousands of years. He argues that the Hindus invented the lunar mansions in 1192 BCE, which means that ‘in that year the moveable Lunar Mansions, or those depending on the sun’s revolution in the tropics, coincided with the fixed or sideral ones of the same name’. At that time ‘the winter solstitial point [which marked the beginning of the year] was in the beginning of both the fixed and moveable mansions Sravishtha’, now known as Dhanishtha, in Capricorn, and the spring equinox was in the nakshatra Bharani, in Aries. However, the Hindus observed that from 1192 BCE to 698 BCE the equinoxes and solstices had precessed by 6°40', with the result that in 698 BCE ‘the beginning of the Lunar Asterism Magha coincided with the middle of the moveable mansion Magha’. The Hindus chose to express this in a different way, by saying that ‘the Rishis got into 6°40' of Magha, that is, the line of the Rishis cut the moveable mansion Magha in 6°40' ...’2

From the standpoint of naked-eye astronomy, Indrasena’s approach would be easy to apply, since it involves drawing a line through the bright stars Dubhe and Merak and extending it to the ecliptic. Sule et al.’s approach (a line from the north celestial pole through the Dubhe-Merak midpoint) and Bentley’s approach (where the line starts at the north ecliptic pole) would be more difficult because there is rarely a star at the north celestial pole and there is no star at the north ecliptic pole. Assumptions about the very primitive technologies of ancient civilizations are, however, increasingly being challenged by new discoveries.

References

Hindu texts often say that a particular important event took place when the seven rishis were in a particular nakshatra. However, the precise periods associated with each nakshatra are uncertain, partly because of the uncertainty regarding the definition of the ‘line of the rishis’, and partly because different systems of lunar mansions have been used at different times. As already mentioned, Aries is nowadays considered the first sign of the solar zodiac, and Ashvini is considered the first sign of the lunar zodiac. But Krittika and Rohini were also regarded as at least the first sidereal nakshatra in earlier times, when the vernal equinox occurred in those mansions. The astronomical references in various ancient Indian texts indicate that they have been edited in the past couple of thousand years but originated in far earlier times.

As currently conceived, the solar zodiacal constellations and signs are only exactly in sync when the vernal equinox is aligned with 0° of the constellation Aries. This occurs at the end of the Age of Aries, because the equinox precesses from east to west, while the earth revolves around the sun from west to east. This means that the sun enters the constellation Aries at 0° Aries once a year, while the equinox enters the constellation Aries at 30° Aries once in every precessional cycle. A complicating factor is that the zodiacal signs are each exactly 30° wide, while the constellations (of which there are really 13)1 vary in width and partly overlap, and there are different ways of dividing them into 12 equal segments.

There is no consensus on where the boundary between Aries and Pisces lies and therefore on the zero-date when the sidereal and tropical zodiacs last coincided. H.P. Blavatsky placed the end of the Age of Aries and beginning of the Age of Pisces in 255 BCE (Poleshifts, app. 1). Indrasena places it in 232 CE. The vernal equinox coincided with the initial point of the Hindu zodiac in 564 CE, this being a point 10 arcminutes east of Zeta Piscium (also called Revati), the principal star of the nakshatra Revati (see Secret cycles, app. 2). This initial point marks the boundary between Revati and Ashvini, i.e. 0° Ashvini and 0° Aries, even though it lies well within Pisces.

The star Revati (white cross near the ecliptic) lay 10' west of the vernal equinox in 564 CE.

Modern Western (Hellenistic) astrology uses the signs of the tropical solar zodiac, which are now out of sync with the corresponding constellations. For instance, the sun passes through the sign Aries from 21 March to 19 April, but it passes through the constellation Aries from 19 April to 13 May. Hindu astrology (known as jyotisha), on the other hand, uses the sidereal solar and lunar zodiacs; in other words, it takes account of precession (ayanamsa).2 Fixing 0° Aries/Ashvini to the vernal equinoctial point seems arbitrary. It reflects the fact that precession was rediscovered by the ancient Greeks towards the end of the Age of Aries. We could just as easily align the solar and lunar tropical zodiacs with the corresponding sidereal zodiacs when the spring equinox enters some other constellation.

Notes

According to the Vishnu Purana, at the beginning of the kali-yuga (the ‘dark age’ or ‘iron age’) the seven rishis were in the nakshatra Magha. The kali-yuga is usually said by Hindu sources to have begun in 3102 BCE (see Secret cycles, app. 1). At that time, the vernal equinox occurred when the sun was in Taurus,1 about 0.8° east of Aldebaran, the principal star of the nakshatra Rohini. On leaving Rohini, the vernal equinoctial point entered Krittika (containing the Pleiades star cluster), also located in Taurus. The equinox coincided with Aldebaran around 3045 BCE, and with Alcyone (the brightest of the Pleiades) around 2340 BCE. That is why Rohini and then Krittika were once considered the first nakshatra.

The Pleiades.

On the basis of Indrasena’s approach, the Dubhe-Merak pointer always cuts the ecliptic in the sidereal nakshatra Purva Phalguni. Using 232 CE as the year in which the sidereal and tropical lunar mansions coincided (i.e. 0° of the sign Aries was aligned with 0° of the constellation Aries), Indrasena concludes that the pointer was in the tropical lunar mansion Magha from 1177 BCE to 210 BCE; his date for the beginning of the kali-yuga is 951 BCE. Adopting Blavatsky’s date of 255 BCE for the end of the Age of Aries would only push the Magha period back 486 years. Using Sule et al.’s approach, the pointer would have been in the sidereal lunar mansion Magha from 1250 BCE to 800 CE.

On the basis of Bentley’s (original or modified) approach to the saptarishi calendar, the line of the rishis does indeed cut the ecliptic in the sidereal nakshatra Magha, but this has been the case for thousands of years. However, if the sidereal and tropical lunar zodiacs were zeroed when the spring equinox entered Rohini, then the saptarishis would also have been in the tropical nakshatra Magha at the start of the kali-yuga.

H.P. Blavatsky refers to Bentley’s interpretation of the line of rishis in the following (corrected) passage about the kali-yuga beginning when the seven rishis were in Magha:

It is, then, the Rishis who mark the time and the periods of Kali-Yuga, the age of sin and sorrow. As the Bhagavata Purana (xii, ii, 26-32) says: ‘When the splendour of Vishnu, named Krishna, departed for heaven, then did the Kali age, during which men delight in sin, invade the world. ... When the seven Rishis were in Magha, the Kali age, comprising 1,200 (divine) years (432,000 common years), began; and, when, from Magha, they shall reach Purvashadha, then will this Kali age attain its growth, under Nanda and his successors.’ This is the revolution of the Rishis: ‘When the two first stars of the seven Rishis (the Great Bear) rise in the heavens, and some lunar asterism is seen at night, at an equal distance between them, then the seven Rishis continue stationary in that conjunction for a hundred years’ – as a hater of Nanda makes Parasara say (Vishnu Purana). According to Bentley, it was in order to show the quantity of the precession of the equinoxes that this notion originated among the astronomers. It was done ‘by assuming an imaginary line, or great circle, passing through the poles of the ecliptic and the beginning of the fixed Magha, which circle was supposed to cut some of the stars in the Great Bear ... [omitted text: ‘which, by calculation, seems to have been the star β’, i.e. Merak]. The seven stars in the Great Bear being called the Rishis, the circle so assumed was called the line of the Rishis; and, being invariably fixed to the beginning of the lunar asterism Magha, the precession would be noted by stating the degree, etc. of any movable lunar mansion cut by that line or circle, as an index’ (Historical View of the Hindu Astronomy, p. 65).2

Bentley strongly denies that the Hindus were practising astronomy in 3102 BCE. He argues that they invented the lunar mansions in 1192 BCE, and that the kali-yuga lasted from 540 to 299 BCE. He accuses those who assign a much greater antiquity to Hindu astronomy of trying to ‘overturn the Mosaic account’, because it would mean that the Biblical story about the creation, Adam and Eve, and Noah’s flood is ‘all a fable’.3

Even though the saptarishi pointer does not move through the lunar mansions at the rate of one nakshatra per century, a calendar based on this assumption can still be used for dating purposes. For example, according to the Vishnu Purana, the kali-yuga began in the reign of Parikshit, when the rishis were in Magha, and when the rishis reach Purvashadha ‘Nanda will begin to reign’ and ‘the influence of the Kali will augment’. Since Purvashadha is the 10th nakshatra after Magha, the period in question would be around 9600 years based on the average rate of precession, but only around 1000 years based on the figure of 100 years per nakshatra. In Hindu books, the period from Parakshit to Nanda is variously given as 1015, 1050, 1115 or 1500 years.4 The meaning is unclear, because ‘years’ might not mean years of mortals.

Notes

Feuerstein et al. argue that the saptarishi calendar, with its 2700-year cycle, is India’s oldest calendar. It is still in use in some regions of India. In Kashmir its starting point has been fixed to 3076 BCE.

Writing about two thousand years ago, Greek historians Pliny and Arrian, who based themselves on reports from the ambassadors at the Maurya courts [322-185 BCE], mentioned that the native historical tradition of India knew of 154 kings, ruling over a period of 6,450 years. When we reconstruct this tradition, it appears that during Mauryan times the calendar was taken to commence in 6676 B.C. This epoch is exactly 3,600 years before the beginning of the current Saptarishi era. Because 360 years were counted as one divine year, it appears that at the end of a divine decade a new cycle – the current Saptarishi era – was thought to have begun.1

There are astronomical references in early Vedic texts that go back before the Age of Taurus (which corresponds to the nakshatras Krittika and Rohini), to times when the vernal equinox occurred in Mrigashira, Punarvasu, and Pushya (Vedic name: Tishya).2

- The principal star of Mrigashira is Meissa (in Orion), which coincided with the equinox around 4060 BCE.

- The principal star of Punarvasu is Pollux (in Gemini), which coincided with the equinox around 6300 BCE.

- The principal star of Pushya is Asellus Australis (in Cancer), which coincided with the equinox around 7300 BCE.

According to Krishna Shastri Godbole, the astronomical observations found in Hindu sacred books go back even further, to 20,000 BCE.3

References

Poleshifts: theosophy and science contrasted