April 2002, last revised Sep 2025

1. Reproductive diversity

2. Human evolution

3. Death and rebirth

4. Virginal reproduction

5. Intersex and hermaphrodites

6. Artificial reproduction

7. Pleasure at a price

8. Leaving sex behind

9. Chastity links

All living organisms have the capacity to produce new organisms similar to themselves. The methods and complexity of the reproductive process vary tremendously, but there are two fundamental types: asexual reproduction, in which a single organism separates into two or more equal or unequal parts; and sexual reproduction, in which a pair of specialized sex cells fuse.1

Asexual reproduction is found in the majority of living organisms, including unicellular organisms, most plants and fungi, and many lower invertebrates. Unicellular prokaryotic organisms (prokaryotic cells have no nucleus), such as bacteria, usually reproduce by binary fission: the parent organism splits into two identical ‘daughter’ organisms, each having the same DNA. In some cases, the cells formed in this way may remain clustered together to form filaments or colonies. Eukaryotic cells (which have a nucleus), including eukaryotic organisms such as protists and unicellular fungi, duplicate into two genetically identical daughter cells through a process known as mitosis; most eukaryotes are also capable of sexual reproduction. Bacteria, fungi and lower green plants (e.g. algae, liverworts, mosses and ferns) can propagate by shedding spores – reproductive cells that produce new organisms without fertilization.

Binary fission in bacteria.

Budding is an asexual mode of reproduction in which a small protuberance or bud forms on the surface of the parent’s body, increases in size, and finally separates and develops into a new individual identical with the parent. In many cases, buds only appear on specialized areas of the body. Budding is characteristic of a few unicellular organisms (e.g. certain bacteria, yeasts and protozoans), but it is also regularly used by a number of multicellular animals (e.g. hydras). Sponges produce internal buds known as gemmules.

A hydra budding.

Regeneration is a specialized form of asexual reproduction. The beating cilia and flagella that propel some single-celled organisms are capable of regenerating themselves within an hour or two after amputation. Some multicellular organisms (e.g. starfish, polyps, zebrafish, flatworms, newts and salamanders) can regenerate new heads, limbs, internal organs, or other body parts if the originals are lost or injured. Many plants are capable of total regeneration, i.e. the formation of a whole individual from a single fragment, such as a stem, root, leaf or even a small slip from such an organ (as in grafting). Among animals, the lower the form, the more capable it is of regeneration. Regeneration is closely allied to vegetative reproduction, the formation of a new individual by various parts of the organism not specialized for reproduction. The highest animals that exhibit vegetative reproduction are the colonial tunicates (e.g. sea squirts), which, much like plants, send out runners in the form of stolons, small parts of which form buds that develop into new individuals.

Regeneration in planarian flatworms.

Sexual reproduction occurs in many unicellular organisms and in all multicellular plants and animals. In higher invertebrates and in all vertebrates it is the exclusive form of reproduction, except in the few cases where parthenogenesis (virginal reproduction) is also possible. A number of unicellular organisms multiply by a primitive form of sexual reproduction known as conjugation: two similar organisms fuse, exchange nuclear materials, and then break apart; each organism then reproduces by fission.

Most multicellular animals and plants undergo a more complex form of sexual reproduction in which distinct male and female reproductive cells (gametes) unite to form a single cell, known as a zygote, which then undergoes successive divisions to form a new organism. In this type of sexual reproduction, half the genes in the zygote come from one parent and half from the other. Whereas asexual reproduction allows beneficial combinations of characteristics to continue unchanged, offspring produced by sexual reproduction inherit endlessly varied combinations of characteristics.

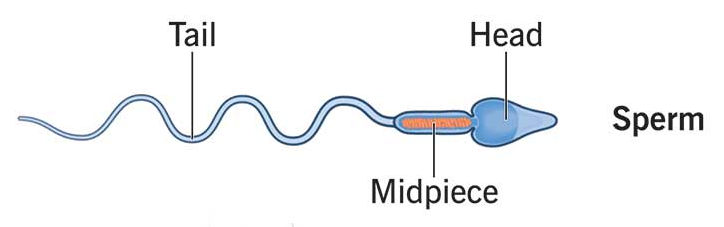

The somatic (nonsex) cells of multicellular organisms are diploid, meaning that they contain two copies of each chromosome – one from the mother and one from the father. Sex cells (sperm and eggs), on the other hand, are haploid, having just one copy of each chromosome. They are produced when somatic cells undergo a complex form of cell division known as meiosis, which reduces the number of chromosomes by half. Meiosis takes place only in testes or ovaries in animals and humans, or anthers and ovaries in plants. When a sperm fertilizes an egg, the egg becomes a zygote, a diploid cell with two full sets of chromosomes, which starts to multiply by mitosis. In humans, DNA in somatic cells is coiled into 46 separate chromosomes; sperm and eggs therefore contain only 23, one of which is the sex chromosome (X or Y).

In the case of plants, wind and insects carry the sperm (contained in pollen) to the stationary egg, or, in a liquid medium, the sperm swims to the egg. In lower animals, sperm and eggs are often deposited in water, but this method is haphazard as only a few of the many sperm discharged reach the eggs. In higher animals, the spermatozoa, contained in the seminal fluid, are deposited in the lower segment of the female reproductive tract. All mammals, reptiles and birds as well as some invertebrates, including snails, worms and insects, use internal fertilization. In many lower multicellular organisms and all higher plants, a sexually produced generation alternates with an asexually produced generation.

Human sperm meet egg.

After fertilization of the egg, the resulting zygote undergoes cell division and differentiation to form the embryo. In most higher plants, the embryo is enclosed in a layer of nutritive material surrounded by a hard outer covering, forming the seed. In most lower animals, the embryo, surrounded by the nutritive material of the former ovum, is enveloped by a leathery or calcareous shell and is extruded from the body of the female. Oviparous animals, such as birds, lay their eggs before the young are completely developed. Ovoviviparous animals produce eggs in shells that hatch within the mother’s body. Placental mammals are viviparous, meaning that they give birth to live young without forming shelled eggs; the embryo is implanted in the uterus and nourished by the mother until almost completely developed.

Parthenogenesis involves the development of an ovum without fertilization. It is common among lower plants and invertebrates, such as water fleas, rotifers, aphids (plant lice), stick insects, ants, wasps and bees. Some species reproduce exclusively by parthenogenesis (such as bdelloid rotifers), but most switch between sexual reproduction and parthenogenesis. In the aphids there is an alternation of generations: parthenogenetic development of eggs (while in the oviduct) takes place in summer when conditions are favourable, while in the autumn, with lack of sunshine and less abundant food, males appear together with sexual reproduction. Sometimes sex cells produce different kinds of individuals according to whether or not they are fertilized. For instance, among common honey bees, a male individual (a drone) arises out of the queen’s eggs if the egg has not been fertilized, and a female (a queen or working bee) if it has. A few kinds of amphibians, reptiles and birds can reproduce parthenogenetically. There are no known cases of naturally occurring parthenogenesis among mammals in the wild.

All pond-living bdelloid (pronounced ‘delloid’) rotifers are females.

Hermaphroditism refers to the presence of organs producing sperm and ova in the same individual. It occurs in the great majority of flowering plants. Most hermaphroditic plants produce male and female elements at different times to ensure cross-pollination, but a few, such as the violet and the evening primrose, are self-pollinated. Hermaphroditism habitually occurs in many invertebrate animals, hagfish and tunicates, and a genus of sea bass. It occurs occasionally in other fishes, and in frogs, toads and certain newts among the amphibians. Hermaphrodite animals are rarely self-fertilizing; in most cases the spermatozoa and ova mature at different times, or the male and female external organs are located so that self-fertilization is impossible. Among the invertebrates, sponges, coelenterates, some molluscs, snails, slugs and earthworms are regularly hermaphroditic. Flatworms have a complete set of male and female gonads in each segment and regularly fertilize themselves.

Flowers are the sexual organs of flowering plants.

Stamen = male reproductive

organ. Carpel = female reproductive organ.

True functional hermaphroditism is rare or absent in higher animals. Animals intermediate in form between males and females occasionally appear, but they are usually sterile, and, when fertile, do not produce both fertile eggs and fertile sperm. Such individuals are often called intersexes. Intersex humans also appear; this category includes all people born with sex chromosomes, external genitalia or internal reproductive systems that are not considered standard for male or female (see section 5).

Although scientists can now describe the physical processes involved in reproduction in great detail, fertilization remains one of the least understood of all fundamental biological processes. The mechanisms involved in parthenogenesis are not understood either. And the seemingly miraculous process whereby a fertilized egg develops into a full-grown organism raises even more questions. Genes do not explain this complex process, as they carry instructions for making proteins, but not for their arrangement into tissues, organs, etc. Something else appears to guide and coordinate embryological development. According to occult science, physical processes are organized and guided from subtler, nonphysical levels of an organism’s constitution; the template for the physical body is an astral (i.e. more ethereal) model-body.2

Explaining how and why sex emerged in the first place poses insuperable problems for orthodox evolutionary theory. The idea that all the intricate components of the male and female reproductive systems could emerge more or less simultaneously, in perfect working order, through purely random genetic mutations, is utterly absurd. Moreover, in the Darwinian struggle to pass on more of one’s genes to future generations, asexuality is twice as efficient as sexuality. This is because an asexual parent transmits all its genes to each progeny, whereas when a sexual organism forms sperm or egg cells, half the genes are removed. As Richard Dawkins puts it: ‘Sexual reproduction is analogous to a roulette game in which the player throws away half his chips at each spin. ... [T]he existence of sexual reproduction really is a huge paradox.’ Another Darwinist says that sex ‘does not merely reduce fitness, but halves it’, and should therefore be ‘powerfully selected against and rapidly eliminated wherever it appears’.3

Sexual organisms face various problems that are avoided in asexual organisms. In addition to the cost of evolving and maintaining the sex organs, there is the possibility of blood Rh factor incompatibilities and tissue rejection between mother and child. Because sperm and eggs are like foreign tissue due to their different genetic makeup, special mechanisms are required to keep the body’s immune defences from destroying its own gametes. Finding a mate, courting and copulating involve risks that place sexual organisms at a further disadvantage compared with asexual organisms. Darwinists therefore have no convincing explanation for the emergence of sexual reproduction.

In the case of asexual organisms, all offspring are essentially clones of the single parent, and differ from it only by new mutations. Sex, on the other hand, creates diversity. Sex shreds every genome in every generation, with the result that all offspring are genetically different (except in rare cases such as identical twins). Mainstream scientists acknowledge that it is difficult to identify any short-term individual benefit in diversity. They also believe that sex would tend to slow the evolution of a species rather than accelerate it, because it breaks up gene combinations randomly, with no regard for their adaptive value.

Another hypothesis is that the benefit of sex lies not in accelerating the spread of beneficial mutations but in more rapidly eliminating harmful mutations. Asexual lineages can acquire more harmful mutations but never less, whereas in a sexual population it is possible for offspring to have fewer harmful mutations than either parent. The problem with this argument is that Darwinism assumes that evolution cannot look ahead to the future; traits can only be selected based on their immediate short-term benefits for the individual. If sex primarily helps to maintain the long-term genetic wellbeing of species, it cannot have evolved by purely Darwinian mechanisms.

References

Occult teachings on the evolution of humanity differ radically from the current theories of materialistic science. Far from having descended from ape-like ancestors through random genetic mutations, the present human form is said to have slowly condensed out of a more ethereal or astral state of matter in the course of many millions of years, just as the earth itself gradually condensed out of the primordial, ethereal nebula.1 And as the outer human body, especially the brain and nervous system, developed, more and more of the faculties of the indwelling soul were able to find expression through the physical form.

According to theosophy, our earliest protohuman ancestors in the present (fourth) round of the earth’s evolution began to develop about 150 million years ago in the mid-Palaeozoic. They were huge ethereal beings, with ovoid bodies, which very slowly declined in size and solidified, and increasingly took on a recognizably human form. The first race was sexless and propagated by fission: a large portion of the body separated and grew into a duplicate of its parent. The second race was asexual and reproduced by gemmation or budding: a swelling or bud appeared on the body of one of these entities, and eventually separated and grew into another individual similar to its parent. At about the midpoint of the second race, these buds increased in number, and became ‘spores’ or ‘seeds’.

The third root-race was initially androgyne. In the earliest stages, reproduction took place by budding, which developed into egg-laying: vital cells were exuded from the outer parts of the body, and collected together to form huge ovoid aggregates or eggs. To start with, the drops of vital fluid were exuded from nearly all parts of the body. Later a single large cell was exuded from a functional part of the organism, which was the root of the later reproductive organs. Hermaphroditism died out in the middle period of the third root-race, some 18 million years ago, by which time the human body was becoming distinctly physical. Individuals began to be born with the predominant characteristics of one or the other sex, until finally only unisexual individuals were produced. While the separation of the sexes was taking place, the awakening of self-consciousness in nascent (and hitherto ‘mindless’) humanity was beginning to accelerate.2

Evidence that humanity was originally hermaphrodite is provided by embryology and physiology. Sexual glands and ducts appear in the embryo in the second month of its development, but they are neither male nor female. Sexual differentiation starts in the seventh and eighth weeks and is fully complete by the 12th week. It is said to be regulated by the sex hormones and control substances secreted by the newly forming ovaries or testes. It proceeds as follows:

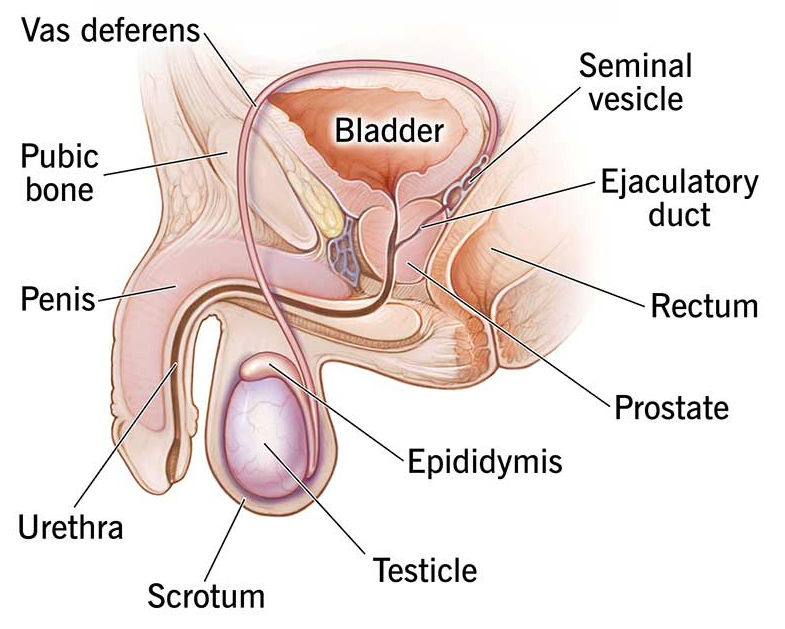

The reproductive organs first develop in the same form for both males and females: internally there are two undifferentiated gonads and two pairs of parallel ducts (Wolffian and Müllerian ducts); externally there is a genital protrusion with a groove (urethral groove) below it, the groove being flanked by two folds (urethral folds). On either side of the genital protrusion and groove are two ridgelike swellings (labioscrotal swellings). ... If testes develop, the hormone they secrete causes the Müllerian duct to degenerate and almost vanish and causes the Wolffian duct to elaborate into the sperm-carrying tubes and related organs (the vas deferens, epididymis, and seminal vesicles, for example). If ovaries develop, the Wolffian duct deteriorates, and the Müllerian duct elaborates to form the fallopian tubes, uterus, and part of the vagina. The external genitalia simultaneously change. The genital protrusion becomes either a penis or clitoris. In the female the groove below the clitoris stays open to form the vulva, and the folds on either side of the groove become the inner lips of the vulva (the labia minora). In the male these folds grow together, converting the groove into the urethral tube of the penis. The ridgelike swellings on either side remain apart in the female and constitute the large labia (labia majora), but in the male they grow together to form the scrotal sac into which the testes subsequently descend.3

The top illustration in this figure shows the undifferentiated

internal reproductive structures in the fetus at approximately six weeks.

The bottom

illustrations show the differentiated (male and female) reproductive structures

at approximately 12 weeks.

This figure shows external genital structures in males and females as they differentiate

during fetal development, and also the typical appearance at birth.4

Fully developed male and female reproductive organs.5

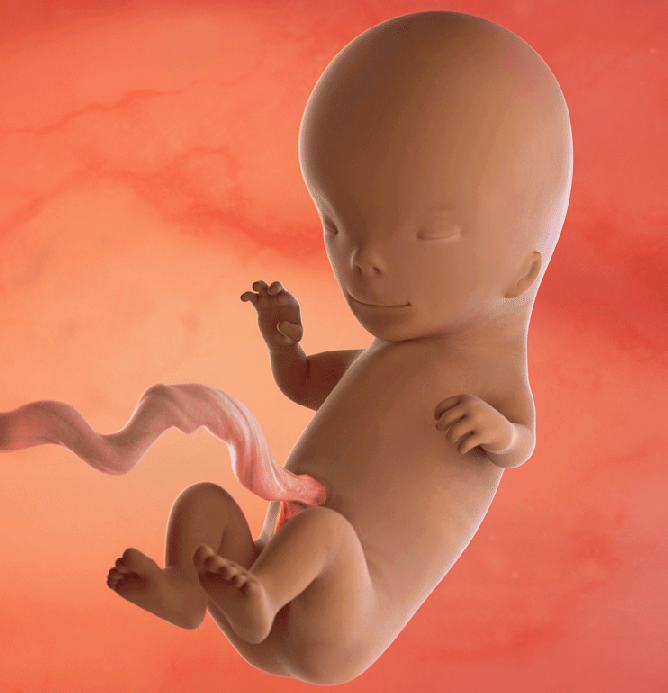

The development of the embryo and fetus in the womb recapitulates

the past development of mankind,* with the first four months corresponding

in several respects to the first four root-races preceding our present (fifth)

root-race. External genitalia appear in the seventh or eighth week but in

a primitive, sexless condition; they become recognizably male or female only

in the second half of the third month,6 corresponding

to the later third root-race. The placenta is fully formed and functional

only after the third month of uterine life.7

*Haeckel’s theory that the development of an embryo (ontogeny) is a condensed repetition of the adult stages of its evolutionary ancestors (phylogeny) went out of scientific fashion long ago. However, S.J. Gould, a proponent of the punctuated equilibrium version of Darwinism, stated that ‘no discarded theme more clearly merits the old metaphor about throwing the baby out with the bath water’; it is undeniable, he says, that ‘phyletic information resides in ontogeny’.8

That the awakening of self-consciousness also took place in this period of evolutionary history is likewise reflected in embryonic development. The brain of a growing embryo develops from the tip of a 3-millimetre-long neural tube, which is formed during the first month. Three to four weeks after conception, the neural tube closes and the brain then grows at a rate of 250,000 neurons per minute for the next 21 weeks. Three distinct regions – a hindbrain, midbrain and forebrain – begin to take shape. By the end of the third month the forebrain, which plays a key role in self-consciousness, has grown particularly fast and now dwarfs the midbrain and hindbrain. At this stage the brain makes up nearly half of the fetus’s weight, but by the time the baby is born, the brain makes up only 10% of its weight. A newborn’s brain consists of around 86 billion neurons and over 100 trillion synaptic connections.9

12-week-old fetus. (babycenter.ca)

The formation of bones is likewise said to have taken place in the third root-race, as the human body became increasingly material. In the fetus, ossification (bone-forming) centres appear in most of the future bones during the third (lunar) month, once they are well formed in cartilage; ossification then continues for the rest of pregnancy.10

Sexual differentiation in the fetus does not lead to the complete disappearance of the reproductive organs of the other sex; rudimentary organs of the opposite sex remain.11 For instance, males have undeveloped, nonfunctional mammary glands, and also an undeveloped uterus and vagina, known as the prostatic utricle or uterus masculinus. The clitoris is a small, nonfunctional equivalent of the penis, and the ovaries correspond to the testes. The testes develop in the abdominal cavity but descend into the scrotum before birth, while the ovaries remain in the abdominal cavity. The testes and ovaries mainly secrete the male and female sex hormones respectively, but they also secrete small amounts of the opposite sex hormones.

Charles Darwin wrote:

It has long been known that in the vertebrate kingdom one sex bears rudiments of various accessory parts appertaining to the reproductive system which properly belong to the opposite sex; and it has now been ascertained that at a very early embryonic period both sexes possessed true male and female glands. Hence some remote progenitor of the whole vertebrate kingdom appears to have been hermaphrodite or androgynous.12

Modern scientists believe that during the early stages of evolution every animal was probably hermaphroditic. Theosophy denies that human bodies gradually evolved from animal bodies, and states that the earliest human stocks, like the earliest animal stocks, were androgynous.

Many myths and legends refer to the androgynous ancestors of present humanity, to the separation of the sexes, and to the first gods being double-sexed.13 Plato in his Banquet (§190) states that an early race of humans were globular in shape and bisexually formed. They were strong and mighty, but ambitious and wicked, so that Zeus cut them in two in order to curb their evildoing and diminish their strength. Since then all mankind has consisted of males and females. An Orphic hymn chanted in the Mysteries asserts: ‘Zeus is a male, Zeus is an immortal maiden.’ Pallas-Athene emerges from Jupiter’s head, and the younger Bacchus is enclosed in his thigh prior to birth. Some statues of Jupiter have female breasts, and representations of Venus-Aphrodite give her a beard to signify the same bisexual nature.

According to the Hindu Puranas, ‘The mighty power became half male, half female’. In one allegory, Brahma (the logos) divides his body into two parts, male and female, and in the latter (known as Vach) he recreates himself as Viraj. Many Hindu images are half male and half female, and have four arms. The ancient Persians taught that humans were the product of the tree of life, growing in androgynous pairs, till they were separated during a subsequent modification of the human form. The Egyptian supreme god Ra is represented as a perfect bisexual being, from which are derived the other gods (Osiris, Horus, Ptah, Ammon, etc.), representing Ra’s various attributes, or the powers of nature. Each of these lesser gods had a female counterpart representing the same individuality in its female state. Similar ideas can be found among the Chaldeans and the Assyrians. In the Hermetic books intelligence is said to be ‘God possessing the double fecundity of the two sexes’.

In the Hebrew book of Genesis, the elohim – usually translated as ‘God’, but actually a plural word signifying the creative powers of nature – first create Adam (early humanity) ‘male and female’, i.e. androgynous (Genesis 1:26-28, 5:1-2). Eve is later made from Adam’s ‘rib’ (the Hebrew word also means ‘side’ or ‘part’). Adam and Eve then eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil (representing the awakening of self-consciousness), and are cast out of Eden (the original, blissful state of unselfconsciousness), and take on ‘coats of skin’ (a reference to the fact that human bodies were then becoming physical rather than astral). Interestingly, the Hebrew word for ‘knowledge’ (daath) also means ‘sexual union’: ‘Now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain’ (Genesis 4:1, also 4:17, 25).

According to theosophy, the sexual method of reproduction was adopted first in the animal kingdom and nature then introduced it in the human kingdom but ‘under protest’.14 This appears to be confirmed by several phenomena. H.P. Blavatsky contrasts the comparative painlessness of procreation among the animals with the suffering and danger it often entails for women.15 Women are among the few mammalian females who have a tough membrane, the hymen, that covers the vaginal opening to a greater or lesser degree. Its forcible rupture means that the first attempt at intercourse is sometimes a bloody and painful experience.

Furthermore, sperm must survive the acidic atmosphere of the vagina and avoid getting trapped in the compact mucus that fills the cervix, the gateway to the uterus. Semen includes an alkaline fluid contributed by the prostate gland that helps to neutralize the acidity of the female reproductive tract. Entrance of sperm into the uterus is also hindered by its quick retraction and closure. Dr Raymond Bernard comments:

How different this is from the direct passage of spermatozoa from the penis to the uterus, which occurs in animals, where the elongated uterus reaches forward until it grasps the penis and aspirates a few drops of seminal fluid.16

Once in the uterus, sperm are attacked and destroyed by the white blood cells of the immune system. Their movement towards the ovaries, at up to 4 millimetres per minute, is also impeded by the downward ciliary current of the minute hairs inside the fallopian (or uterine) tube and the sticky mucus that covers its interior wall. Tens to hundreds of millions of spermatozoa are deposited in the vagina, but only a million enter the uterus, and perhaps only 100 reach the ovum. The vast majority of surviving sperm are then screened and eliminated by a final molecular process. If a sperm succeeds in penetrating the egg, the egg hardens to prevent any more from entering. Only the head of the sperm actually penetrates the egg; it then releases its DNA, which fuses with that of the egg. Eggs that accept more than one sperm will form an embryo with too much DNA, usually resulting in a miscarriage. A couple has around an 18% chance that the man’s sperm penetrates a woman’s egg at her peak period of fertility.17

According to theosophy, the existence of two sexes in the human kingdom is not the endpoint of our sexual evolution. By the end of our fifth root-race, males and females will be disappearing as separate sexes. By the middle of the sixth root-race, which will flourish in a few million years, all of humanity will again become hermaphrodite or double-sexed, and in the final root-race during the present round we shall become completely androgynous. Children will be produced by kriyashakti, i.e. by will and creative imagination – passively in the sixth race, and consciously and actively in the seventh.18 The separation of humans into distinct sexes followed the awakening of self-consciousness and reflects the dual nature or bipolarity of the mind. As the human race evolves and rises out of the lower mind into the higher, the two sexes will disappear.19

These developments will be accompanied by inner and outer changes to our bodies. The sixth and seventh root-races will not have sex organs such as we now have. There will also be changes to our spinal cord. At present, there are two chains of ganglia, or sympathetic cords, on either side of the spinal column. Each is connected with a channel (or nadi) of psychovital force: the sushumna runs through the spinal column, while the ida and pingala are associated with the sympathetic cords. In the next root-race the ida and pingala will develop into two spinal columns connected by the sushumna. In the seventh root-race these two backbones will fuse into one, as our male and female aspects will be fully integrated.20 This will foreshadow the even higher evolutionary state to be reached in the seventh round, when we shall regain our original, divine state of sexless purity, but enriched with the wisdom gained through our self-conscious evolution in the realms of matter.

According to the church father St. Clement, Jesus was once asked when his ‘kingdom’ would come, and replied: ‘It will come when two and two make one; when the outside is like the inside; and when there is neither male nor female.’ G. de Purucker gives the following interpretation.21 ‘When two and two make one’ refers to a time when our psychological nature has become so refined that it coalesces with our spiritual nature. In terms of the sevenfold human constitution, the spiritual nature is the uppermost duad (atman + buddhi, or inner divinity + spiritual intelligence), while the psychological nature is the intermediate duad (manas + kama, or mind + desire). ‘When the outside is like the inside’ means that the dense, physical body will become more sensitive and refined, and therefore better able to express the spiritual faculties of the inner god. The phrase ‘when there is neither male nor female’ speaks for itself: sex is merely a transitory evolutionary stage and is destined to pass away.

References

Materialistic science claims that we are no more than complex, genetically programmed machines. It provides no real insight into the causes of birth, growth and death, or the origin of our self-conscious minds. It cannot even explain the essential difference between a living human being and a corpse – both consist of the same chemical elements.

Occult science, by contrast, recognizes that the physical body is ensouled by subtler ‘bodies’. The physical body dies when the connecting link with our higher centres of consciousness is broken. The physical body proceeds to decay on the physical plane while the astral model-body that holds it together during life, along with the higher astral form in which the lower mind is seated, decompose in different regions of the astral realms surrounding and interpenetrating our physical globe. The speed at which this happens depends on the quality of thoughts and desires in the life just ended. At the ‘second death’ the higher mind or reincarnating soul separates from everything below it and, enclosed within the aura of the spiritual-divine self, enters a blissful, dreamlike state (known as the devachan), in which all the unrealized spiritual hopes and aspirations of the last incarnation are fulfilled, and the noblest experiences of the last life are assimilated and woven into the fabric of our inner nature.

When the spiritual energies generated during the previous incarnation are exhausted, the devachanic dreaming draws to a close, and the attraction to earth life begins to reassert itself. The thirst for material life, the longing to return to familiar scenes and be reunited with past companions, causes us to incarnate on earth again and again. As the reincarnating soul redescends towards its native sphere, its former life-atoms in the astral realms reawaken and start to build a new astral form. The soul’s ethereal energies arouse aggregates of astral and physical substance into forming reproductive cells in the bodies of potential parents, these being people with whom it was closely associated in past lives, and who can provide it with a physical body and family environment suited to its karmic needs. Reincarnating souls may ‘precipitate’ reproductive cells in up to several dozen potential parents, and several different souls may be drawn to the same man or woman.1

If conception takes place, the egg is fertilized by whichever of the male sex cells has the greatest affinity with it at the time.

The human egos awaiting incarnation are exceedingly numerous, so that there may be scores of entities which could become children of any one couple, yet there is always one whose attraction is strongest to the mother-to-be at any specific physiological moment, and it is this astral form which becomes the child.2

If fertilization does not take place, or if it does but pregnancy is later interrupted by abortion, miscarriage or some other accident, the incarnating entity will be psychomagnetically attracted to other suitable parents.

A significant difference between the male and female reproductive systems is that whereas each ejaculation contains an average of 80 to 300 million sperm, only one egg at a time is normally released. And whereas sperm are produced continuously (about 1500 every second), ova are not. Females are born with about 2 million immature eggs (follicles) in their ovaries, but about 11,000 of them die every month prior to puberty. By then, only 300,000 to 400,000 eggs remain. After that, approximately 1000 die each month, with the rate accelerating after the age of about 37.3 Until menopause sets in around the age of 50, one egg matures and is released from its ovary every month and, if not fertilized, passes out of the body during menstruation. According to theosophy, reproductive cells in both males and females may be active or dormant, and a dormant sex cell is vitalized and activated when a reincarnating entity links itself with it.4

Whereas fraternal twins develop from two separate eggs that have been fertilized by two separate sperm, identical twins develop from a single fertilized egg (zygote). In the latter case, at a relatively early stage in its growth, the zygote splits into two separate cell masses which go on to become embryos; these embryos are genetically identical to each other and are always of the same sex. A zygote’s incomplete or late division into two cell masses results in Siamese twins. Triplets may be derived from a single zygote; from two zygotes, one of which divides; or from three separate zygotes. Similarly, quadruplets may originate from one up to four zygotes, and so on. The phenomenon of multiple births suggests that either more than one reincarnating soul can be associated with a particular egg or sperm, or a sperm and egg that fuse are connected with different reincarnating souls, or that one or more additional reincarnating souls may attach themselves to an egg after it has been fertilized.

In humans and other mammals, females have two X chromosomes while males have an X and a Y chromosome. Since an egg can only carry an X chromosome, the sex of an offspring depends on whether the sperm that fertilizes the egg is X-bearing or Y-bearing. Although most males have XY chromosomes and most females are XX, there are exceptions. About one in a thousand men have XXY chromosomes, while a smaller proportion of women have only a single X chromosome. The most important male-determining gene on the Y chromosome is SRY (sex-determining region of Y). Between one in 9000 and one in 20,000 males have two X chromosomes and no Y at all. About two-thirds of these XX males carry the SRY gene on one of their X chromosomes, while the rest have a closely related gene, SOX9. Although X and Y chromosomes are usually termed ‘sex chromosomes’, genes located on chromosomes besides the X and Y chromosomes contribute to sexual development, and genes related to nonsexual traits are located on X chromosomes.5

Contrary to what official biology claims, the sex of a baby is not a matter of chance. It is determined by the lower emotional and mental tendencies and karmic needs which the reincarnating soul embodying in the growing embryo has brought with it from past lives. As a rule, several lives are spent in a body of one sex before changing to a body of the other sex, which happens mainly as a result of the strong attraction to the opposite sex during the last few lives.6 It’s easy to imagine that this changeover may sometimes give rise to some psychological confusion regarding gender.

Males and females who feel they are in the ‘wrong body’ are said to suffer from ‘gender incongruence’ or ‘gender dysphoria’. Nowadays, they can use hormone therapy and/or surgery to alter their external anatomy so that it looks more like that of the other sex. Studies show that 73% to 98% of children who feel that their desired gender does not match their biological sex grow out of their confusion if untreated.7 Transgender individuals often have a range of psychological problems (e.g. anxiety, depression, substance abuse, eating disorders) and have sometimes had adverse childhood experiences (abuse, neglect, etc.). Psychotherapy is a key technique for dealing with such issues, but any approach that doesn’t immediately ‘affirm’ a child’s declared gender and push them towards hormone treatment and mutilating surgery is labelled ‘transphobic’ by the powerful, multibillion-dollar transgender industry.8

Two decades ago transgender individuals were typically middle-aged men, but nowadays around 75% are teenage girls, largely due to social media contagion. In the United States, ‘trans’ children are commonly given puberty blockers until the age of 16, after which cross-sex hormones may be given, followed by surgery after reaching 18.9 In some US states, girls as young as 12 can have their breasts removed; in California the number of such operations rose 13-fold from 2013 to 2023.10 Some European countries have restricted or banned ‘gender-affirming care’ for minors. In 2023 the Russian parliament banned all sex change procedures.

Only 16% of gender dysphoria patients opt for surgery, but up to half of them later suffer complications, such as pain, bleeding, scarring, numbness, infection, difficulty urinating, and loss of sexual pleasure or function.11 Many people remain severely distressed and even suicidal after a sex change operation. A 2023 study found that 81% of transgender adults in the United States have thought about suicide, 42% have attempted it, and 56% have engaged in non-suicidal self-injury over their lifetimes. A 2024 study found that individuals who had undergone sex-reassignment surgery were 12 times more likely to attempt suicide than those who had not. A 30-year Swedish study found that the suicide rate after transgender surgery was 19 times higher than among the general population.12

Up to 20% of transgender people regret their decision to transition, and between 2% and 10% decide to ‘detransition’.13 However, operations like removing the penis, testicles, scrotum, breasts, womb, ovaries and fallopian tubes are irreversible.

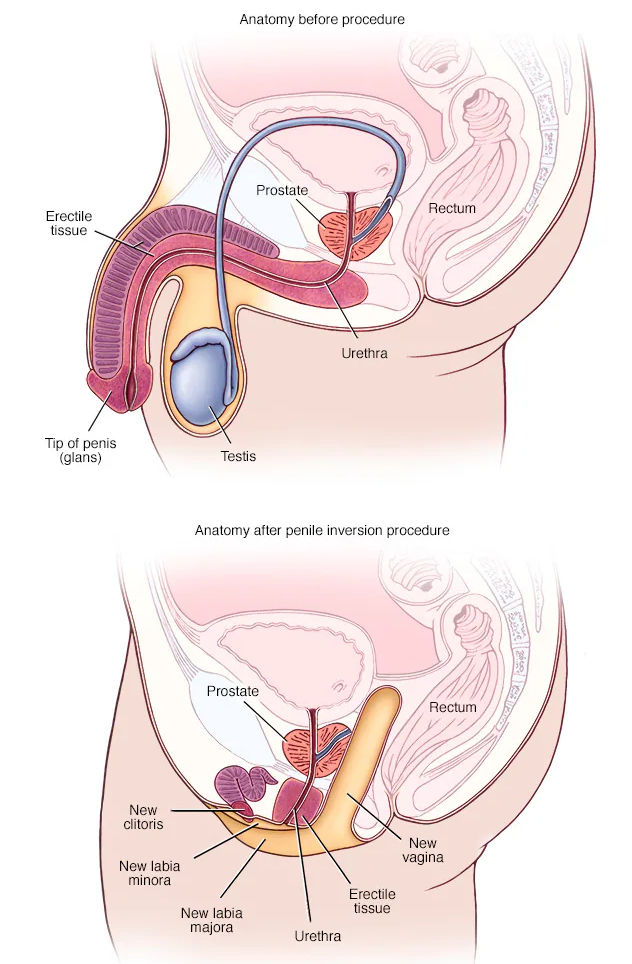

Penile inversion is one method of making a fake vagina (vaginoplasty). Surgeons make a cut between the rectum and the urethra and prostate, and use skin from the scrotum and penis to create a ‘vaginal’ canal. Patients have to regularly insert a dilator into the canal for the rest of their lives to stop it from narrowing or closing, as the body tends to see it as a wound. Initially, this has to be done several times a day, and can be painful and messy. (mayoclinic.org)

To create a fake penis (phalloplasty), large amounts of skin are taken from the forearm, calf or lower abdomen, which can cause significant scarring. The skin is rolled into the shape of a penis and anchored into position above the clitoris. The urethra may be lengthened to allow for urination through the penis. Penetrative sex is not possible unless a semi-rigid or inflatable penile implant is fitted. Phalloplasty carries a high risk of complications, and many follow-up surgeries may be required.14

Repairs to a fake penis that has suffered ‘partial flap loss’. A: dead or damaged tissue

has

been removed.

B: appearance after skin graft. C: appearance after healing. (oaepublish.com)

The human embryo begins as a single cell. Nine months later it has grown to several trillion cells. A question often asked, especially in connection with abortion, is: When does the embryo becomes a living being? Viewed theosophically, at no stage can the embryo or fetus be considered to be anything but alive; it is only the degree of manifest life (and consciousness) that changes. The connection between the reincarnating soul and the body-to-be is established in several stages. Even before conception takes place, a ray of energy from the incarnating soul activates the sex cells in potential parents. The union of sperm and egg marks the next stage, and the embryo then begins to grow, guided initially by the vegetative, vital-astral part of the reincarnating soul. The physical form is built around the astral form, and both attract atoms belonging to the soul in former lives.

Around the fifth month of pregnancy, the fetus can be felt moving for the first time, and this marks the first real entrance into it of the higher attributes of the reincarnating soul.15 By the end of the seventh month, the lower mind is said to be firmly ‘wedged’ in the brain and senses of the fetus.16 After birth, some areas of the brain make new neurons, but more importantly, an intricate network of neural connections is formed, enabling more and more of the latent mental powers of the human soul to be expressed – a process that can continue for most of a person’s life. Mind scarcely begins to function until the seventh year, but is not fully active until the person concerned is of mature age.17

[B]efore, and indeed for a number of years after, birth, the child is only overshadowed by the higher principles of its constitution, the lower principles being the most active in function and expression during the earlier years of life.

Yet at about fourteen or fifteen years of age, ... there occurs the first real entrance of the higher part of the child’s inner constitution into conscious functioning on our physical plane; and from this wonderful hour the enveloping of the growing child and youth with the spiritual-vital aura of the reincarnating ego proceeds progressively and steadily through life into adulthood, and slackens only a short time before natural death – or should do so, and would do so in virtually all cases were it not for the fact that so many human beings live unnatural emotionally and passionally tempestuous lives which weaken the organs of the body and their full and complete functioning.18

References

In cases of parthenogenesis (virgin birth), an ovum starts to divide by itself without fertilization, producing an embryo in which the paternal chromosomes may be replaced by a duplication of maternal ones. Offspring are usually females or sometimes abnormal males. This asexual reproductive method is common among invertebrates, but rare among warm-blooded vertebrates. Until the 1950s no scientists suspected that parthenogenesis could occur in any vertebrate, but all-female species have now been documented in fish, amphibians, reptiles and birds – i.e. in all major orders of vertebrates except mammals.

Artificial parthenogenesis was pioneered by German physiologist Jacques Loeb. In the late 19th century he found that ultraviolet light, ammonia, chlorine, acids, alkalis and alcohols can cause the eggs of sea urchins and other marine creatures to start developing, with no need for sperm. These agents reduce the surface tension of the egg membrane, kicking off a chain reaction (usually started by sperm) that causes embryonic growth. In 1900 he pricked unfertilized frog eggs with a needle and found that in some cases normal embryonic development ensued for a while. In 1936 Gregory Pincus induced parthenogenesis in rabbit eggs by temperature change (cooling of the fallopian tubes) and chemical agents. Artificial parthenogenesis has since been achieved in almost all major groups of animals, by mechanical, chemical and electrical means, though it usually results in incomplete and abnormal development.

Attempts at artificial parthenogenesis in humans have not been successful. The first cloned human embryo was produced in October 2001. Eggs had their own genetic material removed and were injected with the nucleus of a donor cell. They were then incubated under special conditions to prompt them to divide and grow. One embryo grew to six cells before it stopped dividing. The same experimenters also tried to induce human eggs to divide into early embryos parthenogenetically – without being fertilized by a sperm or enucleated and injected with a donor cell – but their efforts met with only limited success.1 Research on human parthenogenesis now focuses on the production of embryonic stem cells for use in medical treatment, not as a reproductive strategy. The creation of human stem cells from unfertilized human eggs first occurred in 2004.2

The scientific view is that:

Mammalian eggs may begin to develop (i.e. to undergo cell division) either naturally or when stimulated. Such ‘embryos’ may have the same chromosome set as the egg (haploid) or two cells may fuse to form the normal adult (diploid) complement. However these cell masses fail to develop far, and die long before birth. No parthenogenetic mammalian embryos have ever been proved to go to term. One reason for this may be the constraint imposed by genomic imprinting in which genes (more correctly, chromosomal segments) from both parents must interact for normal development to take place.3

Experiments on rabbits and mice show that, if an egg is induced to start dividing, the embryo will not survive for long because certain genes will not switch on if paternal genes are absent. Mouse parthenogenetic embryos die by day 10 of gestation. Lack of imprinting leads to abortion because ‘histones, the structures around which DNA is coiled, are lost, as the instructions on how to rebuild them are present in the sperm’.4

In 2004 Japanese scientists succeeded in creating a fatherless adult mouse by combining the nucleus of one female’s egg with that of another.5 An immature egg whose genes had not yet been stamped with an imprint was taken from a mouse genetically engineered to lack a gene known as H19, which is normally subject to imprinting, and a region that would otherwise switch off a gene called Igf2. These two genes are thought to control fetal growth. These steps endowed the egg with a pattern of gene activity similar to that of a sperm. This egg was then fused with a mature egg from a different female. This extremely laborious technique can so far only be used on lab rats. The conclusion drawn from experiments like this is that ‘natural parthenogenesis in mammals is impossible’.6

There is a case of a boy who had his mother’s blood, but not her skin; his blood contained only XX (female) chromosomes, whereas his skin had both X and Y chromosomes. It is believed that he probably originated from an egg that had become an embryo without being fertilized, and that a Y-bearing sperm from his father later managed to fertilize one of the early embryonic cells. ‘Chimeras’ like this are thought to be rare.7

According to mainstream science, human parthenogenesis would only be possible if the changes brought about by sperm-cell imprinting were to occur by ‘random mutation’, or if a ‘random mutation’ eliminated all imprinting. But this is considered ‘highly unlikely’.8 However, it could hardly be as unlikely as the orthodox Darwinian dogma that all the diverse and intricate life-forms on earth have evolved through purely random genetic mutations, followed by natural selection. Various biologists have acknowledged that nature gets things right too often and too quickly to ascribe everything to ‘chance’; there is a purposeful element to evolution that the materialistic paradigm cannot admit to, let alone explain.9

Hermaphroditic animals are mostly invertebrates, such as worms, bryozoans (moss animals), trematodes (flukes), snails, slugs, and barnacles. These creatures are usually parasitic, slow-moving or permanently attached to another plant or animal. Hermaphroditism is thought to have evolved in these creatures because they have trouble finding mates. Hermaphroditism is also said to be ‘favoured by taxa living in borderline habitats, where they can use the energy that would have been allocated for mating to more useful tasks, as well as allowing a quick population increase – this is also the reason why invasive insect species and pests are parthenogenic’.10

If hermaphroditism appears in a species where it aids their survival, it will of course be favoured by natural selection. However, according to Darwinism, new bodily structures and processes, new instincts and ultimately new species appear through random genetic mutations, most of which are harmful and arise from copying errors during DNA duplication; mutations are not made more probable by the fact that they would serve a species’ needs. There are two major problems with this hypothesis: neither protein-coding genes nor regulatory genes contain instructions for building bodily structures or originating new instincts; and even if they did, the probability of all the necessary changes occurring by chance is infinitesimal. Darwinist ideology is a dead end, requiring blind faith in the miraculous power of blind chance.

There is anecdotal evidence that natural parthenogenesis may occasionally occur in humans. There are many instances in which impregnation has allegedly taken place in women without there being any possibility of semen entering the female genital passage.11 In some cases it was found either in the course of pregnancy or at the time of childbirth that the female passages were obstructed. In 1956 the medical journal The Lancet published a report by Dr Stanley Balfour-Lynn concerning 19 alleged cases of virgin birth among women in England.12 The women came forward after the Sunday Pictorial had inquired whether there were any mothers who believed they had given birth to a parthenogenetic child. Such a child would most likely be a girl who closely resembled her mother; it might also be a defective male, but this was 100 times less likely. At that time, DNA tests did not exist, but it was thought that the probability of a genuine virgin birth could be assessed by comparing genetically determined traits and carrying out blood-group tests and skin grafts. The tests were performed by a team of leading doctors.

Eleven of the 19 mother-daughter pairs were eliminated at the first interview because the mothers had thought that a virgin birth meant that the hymen had remained intact after conception and until birth. A further six pairs were eliminated on the basis of blood-group tests, and another pair was thrown out because their eye colour did not match. This left only one mother, Emmimarie Jones (a German by birth), and her 11-year-old daughter, Monica. They were subjected to several additional tests, which indicated that they were genetically alike. Finally, skin grafts were carried out: the graft from daughter to mother was shed in about four weeks, while one from mother to daughter remained healthy for six weeks. Overall, the probability of such a close match between a mother and a daughter produced sexually was less than 1 in 100.

Balfour-Lynn felt that the significance of the skin grafts was obscure. If a parthogenetic child originated from an unfertilized ovum (and not from budding of a somatic cell), it might not have all the genes possessed by the mother, due to meiosis. According to one expert, a skin graft from the child would therefore be expected to take on her mother, but one from the mother would not necessarily take on her child. However, another expert was not satisfied that such a result would be conclusive. There are in fact numerous cases of people rejecting skin transplants from their own skin. Balfour-Lynn concluded:

In such a case as this, rigorous proof is impossible, but it remains that all the evidence obtained from serological and special tests is consistent with what would be expected in a case of parthenogenesis. … Thus, this mother’s claim must not only be considered seriously, but it must also be admitted that we have been unable to disprove it.13

At the time of conception (spring 1944) the mother’s husband was away with the German army and she herself was confined to a women’s hospital. It has been suggested that a male member of staff could have taken advantage of her while she was sedated. However, the mother said that all the staff working at the hospital were women.

This article on Emmimarie Jones and her daughter appeared in the Sunday Pictorial in 1956.

Many tribal societies believe that there are two methods of human

reproduction: the ordinary animal one and a higher one rarely employed – virgin

birth.14 One belief

is that the rays of the sun can fertilize women. In this regard, it is interesting

that ultraviolet rays can cause parthenogenesis in unfertilized eggs of sea urchins.

It is also believed that moon rays, wind, rain and certain types of food can

cause impregnation. In the 19th century the Trobriand Islanders of the western

Pacific insisted that cases of virgin birth still occurred among them.

The possibility of human parthenogenesis is supported by the mysterious phenomenon of dermoid cysts or teratomas.15 These are malformed embryonic growths or tumour-like formations occasionally found in various parts of the body, including womb, ovaries and scrotum. They often contain bones, hair, teeth, flesh, tissue, glands, portions of the scalp, face, eyes, ribs, vertebral column and umbilical cord. They are found in males as well as females, both young and old, including virgins. They appear to be undeveloped embryos and fetuses in various stages of growth. Loeb and several other researchers argued that dermoid cysts may be related to the parthenogenetic tendency of the mammalian egg, catalyzed perhaps by an increase in blood alkalinity. However, the body’s parthenogenetic capacity is now very feeble and the reproductive organs lack the power to carry the reproduction process through to its proper conclusion. Scientists do not understand how, in the absence of any sperm, an ovarian teratoma can end up with two or more sets of chromosomes, two different versions of the same gene, or prostate tissue and phallus-like organs.

It is possible that some cases of human parthenogenesis involve self-fertilization rather than true virgin birth, as there are cases of sperm being produced in women by vestigial, usually nonfunctional, male reproductive glands known as the epoöphoron (parovarium) and paroöphoron, which correspond to the seminiferous tubules of the testicles in males. In some instances, the magnetic influence and nervous excitement occasioned by attempted sexual intercourse may rouse into activity the latent, rudimentary male sex glands so that they secrete semen, resulting in impregnation.16

Prior to the acceptance by the medical profession of the present theory of conception (epigenesis) in the middle of the 19th century, the ovist and aura seminalis theories prevailed, which can be traced back to Pythagoras. According to the ovist theory, the new organism is a product of the egg alone, and the spermatozoon and male progenitor are not essential to the reproductive process. According to the aura seminalis theory, the male supplies only a vital stimulus (an aura or emanation) which initiates the development of the ovum. The aura seminalis theory was rejected after it was established in 1854 that ova were fertilized by the actual entrance of the nucleus or head of the spermatozoa.

However, Loeb’s experiments showed that for fertilization to occur, neither the sperm nucleus nor the spermatozoon itself need enter the egg, or even be in proximity to the egg. He replaced the sperm by alkaline solutions, ultraviolet rays and other stimuli. Alexander Gurwitsch discovered in the 1920s that cells emit weak ultraviolet (‘mitogenetic’) radiation that can cause cell division in other cells at a distance – a finding still resisted by mainstream scientists.17

The desert grassland whiptail lizard (Aspidoscelis uniparens) is an all-female species that reproduces by parthenogenesis. Two females go through courtship and ‘mating’ (pseudo-copulation) rituals resembling those of closely related species that reproduce sexually. How this behaviour causes the eggs of the passive female to enlarge and start dividing is not known.18

The power of sperm to cause fertilization is distinct from their capacity of hereditary transmission. In one experiment, a fertilizing enzyme (occytase) was isolated from spermatozoa and, when added to unfertilized sea-urchin eggs, caused them to develop. This substance is present in mammalian blood, since the addition of ox’s blood to unfertilized eggs produced the same effects. Sperm therefore exercise two independent functions: they can trigger the segmentation of the ovum, and they may convey paternal genetic qualities. The former function can be replaced by chemical substances, while the latter can be dispensed with, in which case the offspring have purely maternal characteristics.19

Eggs show at least a beginning of segmentation under normal conditions. But sperm, which are highly alkaline, appear to accelerate the process by compensating for the excessive acidity of the medium surrounding the egg rather than a chemical deficiency in the egg itself. An acid condition of the blood prevents the parthenogenetic development of ova in the ovaries, while increased alkalinity appears to favour parthenogenetic development.20

Commenting on Pincus’s experiments on artificial parthenogenesis in rabbits, G. de Purucker stated that the means employed had probably thrown the ova back to a condition identical with the hermaphroditism of the early third root-race. Since there is always a double sex in every human or animal of our day, the ova would develop from the double current innate in the mother rabbit and produce offspring much as the hermaphrodites did towards the middle of the third race. He considered such experiments to be ‘abnormal’ and ‘little short of black magic’.21

There are many references in the world’s religions and mythologies to the virgin birth or ‘immaculate conception’ of gods, saviours and sages. While virgin reproduction does occur in the animal world, this mystical teaching also has a twofold symbolic meaning. It can refer to the ‘virgin-mother of space’ giving birth to her ‘mind-born’ son, the manifest cosmos, with its multitudes of beings. And it can also refer to the birth of an initiate’s inner buddha or christ from the virgin or spiritual part of their nature, or from Sophia, eternal wisdom, the virgin-mother of initiates.22 G. de Purucker says:The Christian Church has interpreted these doctrines physically and thus has lost the noble and profound symbolism; but the same mystical teaching and legend is found in other countries: for instance, in India there is Krishna who was born of a virgin, and in Egypt, Horus born of the virgin-mother Isis.23

References

Sex is relative. Among animals, especially cold-blooded ones, males can be turned into females by increased feeding or a change in temperature. In the case of warm-blooded creatures, it can be done by extracting ovaries to turn, say, a hen into a cock. In many species, sex reversals happen naturally. Quahogs (hard-shell clams) are born and grow up male, but later half of them turn female. Slipper shells and cup-and-saucer shells do this too; they commence every season as males, but nearly all of them later pass through a phase of ambisexuality and turn into adult females. Guy Murchie writes:

Sex among these lowly folk seems to depend a great deal on food, since the best-fed individuals turn female the earliest, while the poor scrawny ones get left behind as males (although the opposite happens in the case of oysters). In some species, such as the marine worm Ophryotrocha, if the portly young females are later underfed they revert back into males again. Indeed among most primitive creatures of the sea and practically all insects it is a general rule that the smaller individuals are males and the bigger, fatter ones females, the basic reason being that the essential female function is to produce and feed young, while the only important thing expected of a primitive male is to dart blithely about fertilizing every egg in reach ...1

Fish have evolved the quickest sex-reversing capacity of any animal: some species not only change from male to female as they grow, but a few, like groupers and guppies, develop the ability to switch sexually back and forth within seconds. If two female guppies meet while feeling amorous, one is likely to start turning into a male so he can mate with the other. Occasionally both shift at the same moment, which usually results in a furious fight, with the winner emerging as a female who somehow forces the other to stay male.

As already mentioned, many primitive creatures (including plants) are hermaphrodites, possessing both male and female sex organs. The guppy’s flexibility comes from having both testicles and ovaries with some sort of mechanism that switches the flow from milt to roe. But true hermaphroditism (involving simultaneous sperm and egg flow) is entirely normal among most plants and many animals, from snails, who make love with their feet, to earthworms, which spend hours adjusting and aligning themselves head to tail and tail to head with the aid of a sticky mucus they exude, so that the sperm pores on the 15th segment of each worm coincide with the egg pores on the 10th segment of the other worm.

Mating earthworms.

In times of famine or stress, when such hermaphrodites don’t meet each other so often for cross-fertilization, each one still has the possibility of fertilizing itself by uniting its own sperm and ova. A dynasty of laboratory snails was kept going on self-fertilization for 90 consecutive generations (during 20 years) without noticeable loss of vitality. Some kinds of deep-sea arrowworms actually prefer self-fertilization and use it exclusively.

A curious hermaphroditic creature is the sluglike sea hare, a kind of shell-less snail sometimes two feet long. Its phallus is on the right side of its head and, when playing the male, it puts its head between the finlike fans of a companion playing the female, gradually oozing its member into the genital opening. At the same time as it is a male to one sea hare, it will be female to another on the other side, and as many as 15 of them have been seen linked together in a chain. In a few cases, the chain’s ends work their way round to meet and join, forming a continuous loop – a sort of sexual merry-go-round.2

Hermaphroditus, the ‘son’ of the Greek god Hermes and the

goddess

Aphrodite, origin of the word ‘hermaphrodite’.

Most humans today are born with either a distinctly female or distinctly male sexual anatomy. However, about one person in a thousand is born with an ‘ambiguous’ sexual anatomy, often resulting in disagreement among ‘experts’ as to what their ‘true’ sex is.3 Human hermaphrodites or intersexuals have been reported throughout history.

Intersex bodies present an unusual mix of parts. The organ located where the penis or clitoris is usually found might look like the ‘wrong’ organ, or like something in between the two, or not particularly like either. The genitalia may appear to be of the female type, but the labia may contain testicles. Or the genitalia may look mostly male, but include a seeming vagina. Ambiguous individuals used to be categorized as male pseudohermaphrodites if they had testicular tissue only, as female pseudohermaphrodites if they had ovarian tissue only, and as true hermaphrodites if they had both ovarian and testicular tissue, either separate or combined in an ovotestis. The tissue in question need not be functional in any sense. An interesting asymmetry in true hermaphrodites is that the ovaries are generally found on the left side, and the testes on the right.4

‘Hermaphrodite’ from Cameroon.

True hermaphrodites are very rare (about 1 person in 83,000).5 The vast majority of them have an XX chromosomal basis, though a small percentage exhibit XY chromosomes. A very few have some cells showing XX and others showing XY, and in extremely rare cases cells have a single X chromosome (XO). In every such individual there is also evidence of Y chromosomal material on one of the ‘nonsex’ chromosomes (autosomes). These individuals usually have ambiguous external genitalia with a sizeable phallus so that they are generally reared as males, but they rarely produce sperm. They develop breasts during puberty and menstruate, and in some instances even pregnancy and childbirth have occurred.

Female pseudohermaphrodites have ovaries and exhibit an XX chromosomal pattern, but the external genitalia look masculinized. The most common cause is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), a condition in which the adrenal glands of the fetus produce relatively large amounts of androgens (male sex hormones). Male pseudohermaphrodites have testes and an XY chromosomal pattern, but are born with feminine-looking genitals. There are two main causes: testicular feminization syndrome or androgen insensitivity syndrome; and 5-alpha-reductase deficiency. In the latter case, the body develops along more masculine lines at puberty; the testes often descend into the assumed-labia, and the penis/clitoris grows to look and act more like a penis. Women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome are technically ‘male’ pseudohermaphrodites because they have internal testes rather than ovaries. However, this label seems inappropriate because these women often have primary and secondary sexual characteristics typical of other women and feel they have normal (external) female bodies.

Former South African athlete Caster Semenya has always identified as female. She is a two-time Olympic champion (2012 and 2016) and three-time world champion over 800 metres. After winning the women’s 800 and 1500 metres at the African Junior Championships in 2009 with impressive times, her sex was called into question. Tests revealed that she has a condition known as 46 XY 5-ARD (5-alpha-reductase deficiency). Although she has typical male chromosomes (46 XY), she has a vagina, but no uterus or fallopian tubes, and she also has internal testes instead of ovaries, resulting in testosterone levels typical of males. Initially she was allowed to continue competing, but in 2019 World Athletics introduced new rules restricting testosterone levels in female runners. She would now have to take testosterone-reducing drugs to participate in competitions, but decided not to as the drugs she had taken from 2010 to 2015 had made her feel constantly sick.6

Ambiguous genitalia can also result from other conditions. In Klinefelter’s syndrome, for instance, the presence of several X chromosomes and one Y chromosome sometimes results in sexual ambiguity. Moreover, many babies are born with relatively unusually formed genitalia but are not categorized as ambiguous or intersexed. Unquestioned females are sometimes born with relatively large clitorises, and a large number of male babies – perhaps one in every one or two hundred – are born with hypospadic penises, meaning that the urethra exits some place other than the tip of the glans. Operations are often performed very early on hypospadic penises, and large clitorises are often surgically reduced.7

Intersex surgery: before (A) and after (B). (slidesharecdn.com)

(For more graphic photos, click here.)

The term ‘pseudohermaphroditism’ was first used in 1876, long before the discovery of X and Y chromosomes, and the term ‘intersexuality’ was introduced in 1923. However, most intersex or hermaphrodite people think of themselves as being either boys/men or girls/women. A multidisciplinary meeting of medical and nonmedical experts in Chicago in 2005 (the Chicago Consensus) proposed that congenital conditions associated with atypical development of chromosomal, gonadal or anatomical sex should be called disorders of sex differentiation (DSDs), and that terms such as intersex, hermaphroditism and pseudohermaphroditism should be dropped. In the new terminology, male and female pseudohermaphroditism are known as 46,XY DSD and 46,XX DSD respectively, and true hermaphroditism is known as ovotesticular DSD. Since ‘disorder’ implies that any differences of this kind are pathological, the term ‘differences of sex development’ is also used, while some people still prefer the term intersex.8

Intersexuals have traditionally been regarded as freaks in need of a medical-technological ‘fix’, but this attitude has increasingly been challenged in recent decades.9 The orthodox medical response has been to create a ‘believable’ masculine or feminine anatomy via plastic surgery and hormonal therapy as soon as possible after birth. CAH is a metabolic disease and certainly requires treatment as it can save a child’s life and fertility. Likewise, androgen insensitivity needs to be diagnosed as early as possible so that the testes of androgen-insensitive people can be carefully watched or removed, as there is a high risk of cancer. However, ambiguous genitalia are not diseased, and the narrow definition of ‘normality’ has resulted in an extraordinary number of risky surgeries on unconsenting children. Complications include scarring, infections, loss of feeling, and psychological trauma.10 Nowadays, both medical doctors and intersex advocates increasingly recommend not assigning a gender identity in infancy and delaying nonessential surgery until the person in question is old enough to express a gender identity and participate in medical decisions.11

As already mentioned, the tradition that the early ancestors of the human race were androgynous is widespread among all races of the world. Even today, 100% maleness or femaleness does not exist as each sex contains the rudimentary organs of the opposite sex; in this sense we are all intersexuals. Some researchers have argued that hermaphrodites represent an atavistic reversion to a primordial type. From a theosophical standpoint, hermaphroditism can also be seen as a foreshadowing of what is to come.

It is noteworthy that males sometimes have cycles closely resembling the female menstrual cycle in length and nature. In rare cases, males may even menstruate periodically, with blood being discharged from various parts of the body, usually the nose or urethra.12 There are also instances of males having breasts as large as a female’s and as functionally active, so that they are able to suckle offspring.13

According to theosophy, the separation of the sexes in the third root-race took millions of years. Many details of the different reproductive stages passed through by the third root-race, and the corresponding changes in anatomy, are lacking, but the general scenario seems to have been as follows.14 In the early third root-race, humans had no external sex organs such as now exist. Initially ‘vital cells’ were exuded from all parts of the body and coalesced into a huge egg, in which the fetus gestated for several years. Later an egg was laid that had been formed within the body. The idea that early (semi-astral) humanity was egg-laying is not as strange as it may seem; the modern method of reproduction is essentially a modified, internal, microscopic version of the same thing. As some point, offspring began to be born with external sexual organs, and initially these individuals were probably true functional hermaphrodites or male-females, who fertilized one another and could play the role of male or female. Gradually this form of true hermaphroditism gave way to pseudohermaphroditism and finally to unisexuality. In humans today, males have nine orifices and females 10. Blavatsky says that, prior to the separation of the sexes, 10 orifices existed in the hermaphrodites of the third race, first potentially, then functionally.15

The terms ‘hermaphroditic’ and ‘parthenogenetic’ are sometimes used interchangeably in theosophical literature to describe both the past and future modes of reproduction, whereas hermaphroditism is normally regarded as a sexual mode of reproduction and parthenogenesis as an asexual mode. However, this distinction may be somewhat artificial. Even when there is no physical fertilizing agent, some sort of ‘male’ potential must ‘activate’ the egg, and an organism in which such a potential resides is in a sense hermaphrodite. (G. de Purucker says that there is a double sexual current in every human and animal today.) As mentioned in the previous section, where parthenogenesis occurs in humans today, either the rudimentary seminal vesicles in females may produce sperm, or fertilization may involve a subtler agent, as postulated in the aura seminalis theory. In both cases, attempted (but nonprocreative) sexual intercourse with a male partner may sometimes act as trigger. Dermoid cysts indicate that a weak potential for parthenogenesis is also present in males.

In the future, male and female bodies will probably grow more alike, and the incidence of both pseudo- and true hermaphroditism will increase, until hermaphrodites are finally in the majority and single-sexed individuals begin to be looked upon as abnormal. Cross-fertilization will eventually be replaced by self-generation.

References

One in six couples worldwide experiences some form of infertility problem at least once during their reproductive lifetime.1 Assisted reproductive technology (ART) aims to help them have children. The most common procedure is in vitro fertilization (IVF): a man’s sperm and a woman’s eggs are brought together in a laboratory dish, and the resulting embryo is then transferred to the woman’s uterus. Induced ovulation involves treating a woman with hormones to stimulate her ovaries to release eggs. Intrauterine insemination (IUI) is used to help get underperforming sperm or eggs in the same place at the same time. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) involves injecting a single sperm into an egg. Sometimes sperm or eggs are obtained from donors, or an embryo is implanted in the uterus of a surrogate mother.

The first ‘test-tube baby’ was born in 1978. Since then an estimated 10 million IVF babies have been born. Today, around 1 in 50 babies born in the UK, and 1 in 100 babies in the US, starts life in a lab. Success rates with IVF and ICSI are only around 30% at best. After age 45 the chance of pregnancy is close to 0%.2

To persuade the ovaries to release multiple eggs, hormones are administered in high doses. This can cause premature menopause, uterine cancer and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), where the ovaries become swollen and painful.

Fluid may accumulate in the abdominal cavity and chest, and the woman may feel bloated, nauseated, and experience vomiting or lack of appetite. ... Up to 2% of women develop severe OHSS characterized by excessive weight gain, fluid accumulation in the abdomen and chest, electrolyte abnormalities, over-concentration of the blood, and, in rare cases, the development of blood clots, kidney failure, or death.3

To harvest eggs, a long, thin needle is passed through the vagina to the ovaries and used to suck the fluid out of mature follicles, or egg-containing sacs. This invasive procedure entails a risk of bleeding, infection, and damage to the bowel, bladder or blood vessels.

Trade in eggs has grown exponentially in response to demand.

As in the case of wombs-for-rent, there is scope for abuse. Women from poor socio-economic backgrounds may submit to – or be coerced into – successive egg donations to make money ... This phenomenon has been called ‘fertility tourism’ or, in its most nefarious forms, ‘egg trafficking’.4

In one case, a Stanford student who had agreed to donate eggs for a fee of $15,000 experienced a rare adverse reaction to one of the fertility drugs. She suffered a massive stroke, which left her in a coma for eight weeks with long-term brain damage.5

In the US and the UK most adoption agencies prefer to place very young children with couples in their 20s or early 30s. For older, single women the only real option is to turn to international adoption bureaus, which charge $32,000 to $64,000 for their services, while donor sperm costs $1000-$1500 and donor eggs $20,000-$60,000.6

To prepare for pregnancy, surrogate mothers are pumped full of hormones, putting them at risk of long-term liver problems. They also face the usual risks of pregnancy, such as toxaemia and haemorrhage. A woman who carries to term a child not genetically related to her and has had no previous exposure to the genetic father’s antigens faces an as yet unknown threat to her immune system. Surrogacy is a lucrative business in poor countries like India, where women are paid between $6000 and $10,000, equivalent to about 15 years’ wages on average. Couples from countries like the UK, US, Germany, Japan and Australia make use of these services because, even with travel costs, they pay a third of what it would cost in their own countries. Women in India are 69 times more likely to die from childbirth-related issues because of inadequate access to good medical facilities.7

A study found that the percentage of babies with birth defects (including cerebral palsy and heart defects) was 7.2% after IVF and 9.9% after ICSI, compared with about 6% of babies conceived naturally. However, most of the increased risk of birth defects was due to parental factors, such as the mother’s age, smoking status and conditions during pregnancy.8 There is evidence that children conceived by ART have an increased incidence of growth abnormalities associated with genetic imprinting (imprinted genes are contributed by only one parent).9 All assisted reproductive technologies increase the chance of preterm birth, low birth weight and multiple births, with all the risks this entails.10 Following ART procedures, miscarriage occurs in nearly 15% of women under 35, in 25% at age 40, and in 35% at age 42.11

References

In 2020 9.9% of babies worldwide were born prematurely, with the highest rate (13.2%) being found in southern Asia, and the lowest rate (6.8%) in eastern and southeast Asia.1 Since 1880, premature babies have been enabled to survive by placing them in incubators. These provide warmth and humidity, but nutrients and oxygen have to be delivered via tubes inserted into the baby’s body. The babies are usually sedated some of the time to stop them pulling the tubes out or to reduce discomfort or pain. Infection around the tubes is a serious risk.

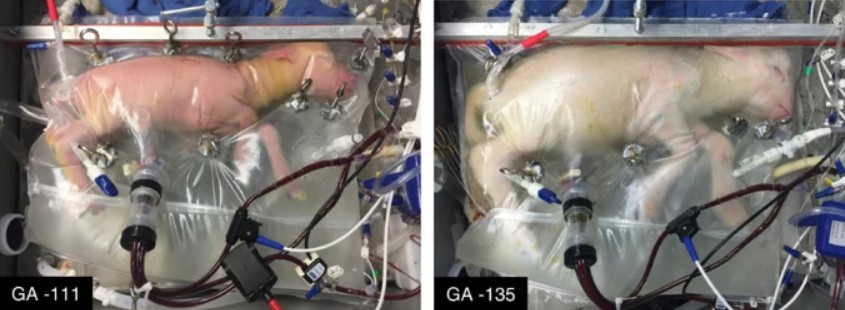

Today, a preterm fetus can survive when removed from the mother at a gestational age of slightly less than 22 weeks – just over half the length of a normal 40-week pregnancy. However, exposure to air causes numerous complications and negative long-term outcomes for infants born before 28 weeks. That is why there are efforts to develop an artificial womb.